Equestrianism is popular worldwide, with millions of horses and riders participating in competitive horse sports and non-competitive leisure riding (Williams and Tabor, 2017). Horse sports and related activities contribute substantially to many global economies including the United Kingdom, where the equestrian sector was reported to have contributed £4.7 billion to the economy in 2019 (British Equestrian Trade Association, 2019). The British Equestrian Trade Association reports that approximately 3 million people regularly ride horses in the UK, with 374 000 horse-owning households. However, despite the continuing popularity of horse riding and horse sports, the high-risk nature of some equestrian activities, combined with the potential for them to cause injury or fatalities to the horses and people participating in them and the increased scrutiny of equine management and training, is resulting in increasing public scrutiny (Campbell, 2021; Douglas et al, 2022; Wolframm et al, 2023). Non-equine stakeholders are questioning humans' right to use horses for leisure and recreational purposes, while equine stakeholders often query if traditional training and management practices are ethical and necessary (Williams and Marlin, 2020; Douglas et al 2022; Brown et al, 2023). This debate has evolved, and the question of how equestrianism demonstrates it has a social license to operate in the modern era is now commonplace across all sectors of the equestrian industry. This review will reflect on what it means to have a social license to operate as a concept. It will also consider the status of equestrianism's social license to operate and what this means for different stakeholders in the equine sector. Finally, the future development of horse sports and their social license to operate will be discussed.

What is a social license?

The concept of a social license arose to showcase societal acceptance of an industry, organisation or sport. The first documented discussions about an industry's social license to operate arose in resource-based industries, specifically mining, in the late 1990s to showcase their legitimacy to users and consumers (Gehman et al, 2017; Douglas et al, 2022). The development and implementation of a social license to operate in mining aimed to protect the health and safety of workers, alongside protecting the communities and environments affected by mining activities, as industry practice at that time was deemed to be causing environmental damage and unethical (Duncan et al, 2018).

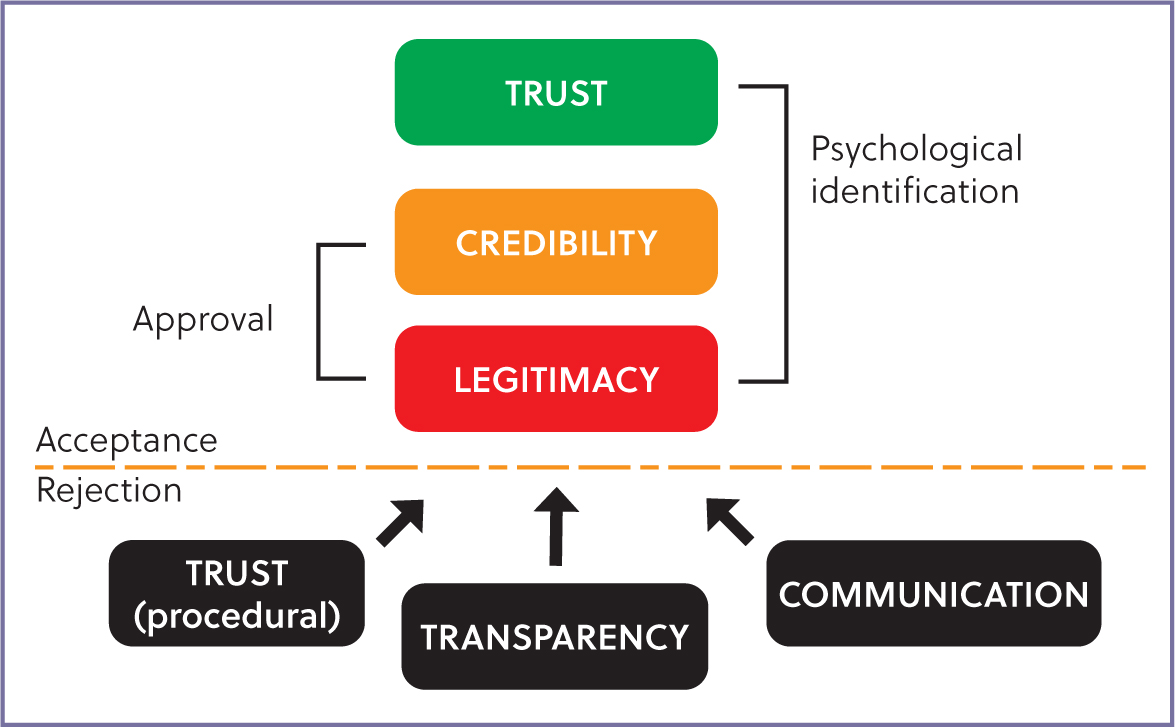

In essence, breaking down the definitions of each component within a social license to operate gives a clear indication of what a social license to operate is (Box 1). Most social licenses comprise of four key contexts that are integrated into development: legitimacy, trust (procedural), transparency and communication, underpinned by a transparent approach to practice and effective communication strategies (Duncan et al, 2018). It is also important to understand that a social license is not an ‘all or nothing’ or static ‘complete it once and it is in place forever’ concept (Duncan et al, 2018; Douglas et al, 2022). Public acceptance of activities is likely to vary on an individual level and may sit at any point on a continuum, where an individual person has complete trust in the credibility of an area (psychological identification - perhaps an established equestrian competitor), or sit at the opposite end of the scale, where individuals reject the legitimacy of an activity completely (Figure 1). This perspective would represent the view of Animal Aid, for example, who are universally opposed to horse-racing (Prno and Solcombe, 2012; Williams and Marlin, 2020). Individual perception of an acceptable social license for an area is also likely to evolve with a person's own experiences and education, but will also be influenced by the media and broader societal perspectives (Fiedler, 2019). Therefore, within the public consciousness for specific social license areas, the opinions of different stakeholder communities will vary, with the majority judgement most likely to take precedence.

Box 1.Social, license and operate definitions (Duncan et al, 2018; Douglas et al, 2022; Oxford English Dictionary, 2023)Social: relating to society or its organisationLicense: authorise the use, performance, or release of (something)Operate: (person/organisation) control the functioning of/to function properly (process/system)Social license to operate: a dynamic and evolving framework for an industry, sector or sport that defines the boundaries in which they should operate to protect all stakeholders involved within it, and which they need to obtain and maintain. Providing ‘the privilege of operating with minimal formalised restrictions’

Social license to operate in equestrianism

Equestrianism is steeped in history and tradition, which continue to influence how humans interact with horses in the modern era (Williams and Tabor, 2017). While horses arguably retain some element of agency – the ability to act autonomously and control their own lives – given they are sentient and can utilise their size to exert some independent movement, humans are generally the lead protagonist that control the direction of travel in the horse-human relationship. People therefore have a duty of care to ensure they manage their horses responsibly, and should engage in practices which promote equine health and welfare and should turn to ethical equitation practices that prioritise a horse-centric and welfare promoting approach (McGreevy and McLean, 2005; Williams and Tabor, 2017). These are fundamental aspects which would underpin a social license to operate for equestrianism (Heleski, 2023).

Researchers across equine welfare and equitation science fields have called for horse riders, owners and trainers to discharge their duty of care and engage in ethical, evidence-informed practices to the horses they interact with for more than two decades (McLean and McGreevy, 2010; Randle, 2010; Waran and Randle, 2017; Williams and Tabor, 2017). The concept of social legitimacy and social license for industries involving animals such as horse-racing has been debated since 2010; a specific equestrian social license to operate that is more focused around the welfare of all horses, as opposed to just horses used in professional sport, was highlighted by Fiedler and colleagues at the 19th International Society of Equitation Science conference in 2019 (Fiedler et al, 2019). During this time, the use of horses – particularly in horse-racing – has been the subject of public scrutiny with high profile horse fatalities in races such as the Grand National and the use of the whip fuelling debate. More recently, televised incidents of falls and fatigued horses in eventing and inappropriate rider and coach actions in the modern pentathlon during the Tokyo Olympics have led to questions on how horse welfare is managed across horse sports, highlighting that evaluation of social license broader than horse-racing is warranted. Equestrians may or may not agree with broader public perception, however, whether they do or not is to some extent a moot point, as Fiedler commented (2019): ‘The public's ideas aren't always grounded in scientific fact. But whether the public is right or wrong, their perceptions of animal welfare in horse sport are what matters.’ Therefore, the equestrian sector finds itself at a critical crossroads with the public questioning if horses should be used for human activities; the framework of a social license to operate offers a working solution to safeguard the future of horse sports and recreational equestrianism.

Social license to operate and equine welfare

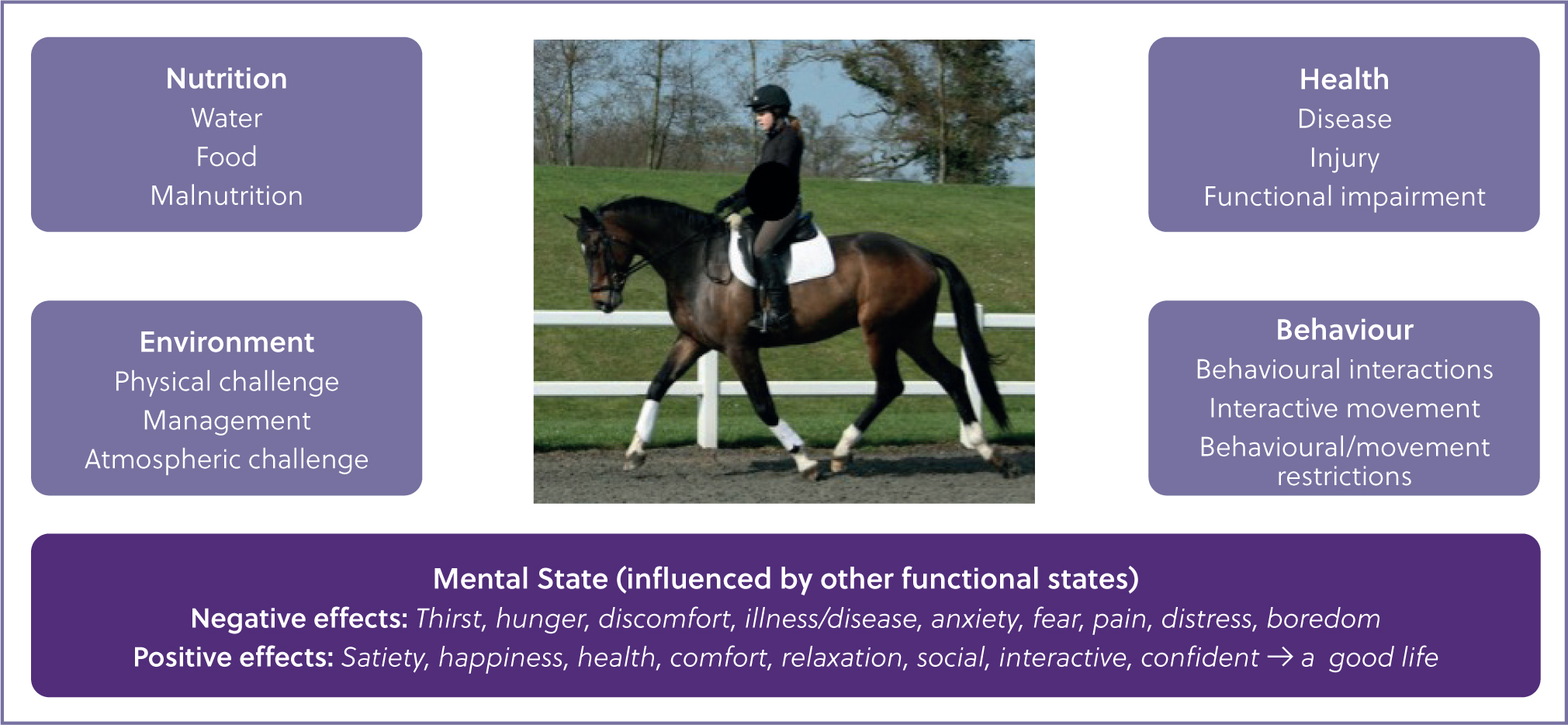

The welfare of horses is predominately in the hands of the humans that manage and interact with them (Williams and Tabor, 2017; Heleski, 2023; Wolframm et al, 2023). As a sector, horse owners and handlers need to provide opportunities for animals to ‘thrive’ and live ‘a good life’ rather than just survive (Mellor, 2016). Applying the enhanced Five Domains framework (Figure 2) for animal welfare to assess equine quality of life, including evaluation of a horse's mental state, could be a good, positive starting point for equestrians to critique their practice (Mellor et al, 2020). The Five Domains model has been adapted across multiple species over the last 25 years. The latest version of the model includes the five domains:

- Nutrition

- Physical environment

- Health

- Behavioural interactions

- Mental state

A key objective of the model is to focus welfare assessment on considering both negative and positive experiences (or affects) within domains 1–4, and how these interact to determine an animal's overall mental or affective state (domain 5) to provide a measure of an animal's overall quality of life. Another key element in the model is the consideration of behaviour (domain 4) not just as behaviours essential for an animal to survive, but to also evaluate the positive and negative impact of environmental interactions, interactions with non-human animals and human-animal interactions and how these influence welfare. As a result, the revised model is more nuanced, and while individual subjective assessment of factors within each domain will influence welfare assessment, taking this approach provides a more balanced evaluation of animal welfare and whether an animal, on balance, has a good life (Mellor et al, 2020). Many equestrian federations and organisations are starting to embrace this concept and integrated equine welfare as a strategic priority – for example, ‘Horses first’ is an International Equestrian Federation core value.

Key policy making organisations such as the British Horse-racing Authority and the International Equestrian Federation have also proactively established independent bodies, the Horse Welfare Board and Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission respectively, to lead the way to ensure horses have a good quality of life for their sectors. Recent consultation with just under 28 000 equestrians (Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission, 2022) and the general public (Heleski et al, 2020; Douglas et al, 2022) has consistently identified equine welfare, specifically how horses' mental wellbeing, physical condition and health are adequately prioritised, as a critical concern (Box 2).

Box 2.Key areas of public concern in horse racing and horse sports (Heleski et al, 2020; Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission Survey, 2022)

| Horse-racing | Horse sports |

|---|---|

| Equine welfare | The other 23 hours |

| Surfaces: injury and fatalities | Tack and equipment |

| 2-year-old races: age thoroughbreds enter the sport | Training and riding practices |

| Race day medication | Physical stress and injuries |

| Other drugs: doping | Recognising emotional stress |

| Whip use | Competitive drive; horse as a number |

| Aftercare (former racehorses) | Overworking/not fit to compete |

However, the complexity of the horse-human relationship and the multiple ways humans engage with horses recreationally in sport, and as agricultural and working animals should not be underestimated, and developing a universal social license to operate framework for equestrianism is not a simple task (Williams and Marlin, 2020). Equestrian sport and practice are steeped in tradition and many existing training and management practices remain based on anecdotal and historical methods rather than scientific evaluation of their effectiveness (McLean and McGreevy, 2010; Williams and Tabor, 2017). An effective starting point to embed a social license to operate may be to work towards developing an evidence-based approach to legitimatise the management, training and ridden practices adopted with horses to demonstrate that these are fully justified and their purpose clearly articulates with the outcome desired. Evidence-based practice should be the foundation of practice for individuals working and engaging with horses, to inform their decision-making and enable them to make a moral judgement as to whether their decisions are ethical and safeguard the horse (Waran and Randle, 2017; Williams and Tabor, 2017). Taking this approach would also underpin the concepts of trust and transparency within the social license to operate model. Trust must also exist in procedural and regulatory contexts, with key organisations leading the way across equestrianism, but it should equally be evidenced through the duty of care between individuals and the horses in their care (Williams and Marlin, 2020). Once trust is established through an evidence-based approach to decision-making, then transparency should follow as the industry would essentially have nothing to hide and should hopefully promote public acceptance of horse sports and equestrian activities.

Education and research also have a key role to play within the final construct of the social license to operate model: communication. Despite the need for evidence-based practice there are many areas of equestrianism where research to provide empirical data to inform decision-making is lacking. Alongside this, where research does exist, effective communication to the people who would use it in the real-world in a user-friendly format and without judgement of current practice, is sadly often lacking. The veterinary sector has a key role to play in this element of social license to operate. Previous studies have demonstrated that general equestrians have only a moderate insight into their abilities and think they know more than they really do in practice (Warren-Smith and McGreevy, 2008; Marlin et al, 2018). This level of over-confidence could have serious consequences for horse welfare and emphasises the need for improved education at an individual horse owner or rider level, an area which equestrian stake-holders also identified as being much needed (Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission, 2022). Interestingly, recent work evaluating international equestrians found that veterinarians are considered a key trusted source of information regarding how to manage horse health and welfare (Williams et al, unpublished data). Veterinarians are also well placed to support horse owners prioritise best practice approaches to managing horse health. They could also help educate owners to be able to recognise that abnormal or conflict behaviours can indicate pain and perhaps underlying health conditions in the horse and warrant further investigation, rather than being a training issue (Figure 3) (Williams and Tabor, 2017). This position of trust places equine veterinarians and veterinary nurses in a strong position to support their clients by translating emerging research into best practice approaches to manage equine health and welfare, to be a source of unbiased and trusted information and a key gatekeeper for the horse within equestrianism's social license to operate. Veterinarians also have their own responsibilities within the evolving equestrian social license to operate. Practices which were considered normal historically (such as pin-firing tendons) have all but disappeared (Allen et al, 2023), but other areas of contemporary management within horses may not stand up to public scrutiny and may call the veterinary industry's social license to operate into question (Blea, 2020). For example, can the regular use of joint injections and other medications to manage performance in sport horses be justified, the high injury rates in athletic horses or the high incidence of obesity observed in horses be ratified or keeping horses without opportunities for social interaction and free exercise (Figure 4)?

The future of equestrianism's social license to operate

The increased scrutiny of human interaction, management, use and care of horses as equestrianism continues to develop its social license to operate requires stakeholders across the sector to reimagine measures of success in horse sports, and ensure equine welfare, health and longevity take equal precedence with performance metrics. Douglas et al (2022) advocate that equestrian culture would benefit from a shift in perception, where stakeholders first ask, ‘Should I?’ before they ask, ‘Can I?’ (Campbell, 2019). This approach is critical and needs to be actively embraced by all equestrian stakeholders if the social license to operate is to be believed by the public (Heleski, 2023). This perspective was echoed by the respondents of the Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission survey (2022) who indicated that they believed that horses will be involved in sport in the future but only with modifications to ensure their welfare is improved.

The International Equestrian Federation's Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission outlines their vision for the future across 24 recommendations, including sharing a ‘good life for horses’ vision, and underpinned by a horse-centric approach which has its foundations in ethical and evidence-based equestrianism embedded in an infrastructure that establishes a trusted and pro-active culture of accountability, responsibility and transparency (Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission, 2023). This requires the horse industry to come together and unite behind a common goal: placing the horse first. Key enablers are needed to support this vision, including increased research to generate evidence to inform practice and regulation across the sector, increased education for all levels of stakeholders to inform decision-making to promote a good life for horses, to enable accurate welfare assessment and an informed lead from policy makers and regulatory bodies to act as an advocate for the horse across competitive horse sports (Williams et al, 2019; Douglas et al, 2022; Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission, 2022).

While education and science could prove important enablers to move social license to operate forward in horse sports, several potential inhibitors to establishing a credible and trusted social license to operate also exist. Social media offers a lens on all aspects of the equestrian industry: the good, the bad and the ugly, with a picture or video having the potential to reach incredibly large public audiences. Unfortunately, ‘the bad’ and ‘the ugly’ often generate more newsworthy stories and gain more traction with the media, translating to increased public attention compared to ‘the good’. Individual equestrian stake-holders (and others in the industry) need to showcase ‘the good’ via effective communication, education and engagement with evidence-informed practice and ethical approaches to horse management and training. They also need to proactively challenge poor practice, in a non-judgemental and supportive way, remembering that a substantial proportion of equine welfare issues reported are associated with neglect due to owner or rider ignorance rather than malicious intent (Hemsworth et al, 2015). Where it is clear no evidence base exists to determine if a piece of tack, training or clinical approach or management practice is beneficial to the horse, then there should be targeted mechanisms and support from equestrian policy makers and governing bodies to support research to generate this. There is a clear need for increased transparency to showcase the good, highlighting the incredible bonds that exist between people and horses, and the good practice which already exists, while challenging the bad and myth busting the ugly.

It should also be recognised that words have power and the language used within debate can evoke strong emotions and influence perception of social license to operate. The whip debate is a good example of this. A whip is defined as a noun as ‘…a strip of leather or length of cord fastened to a handle, used for flogging or beating a person or for urging on an animal’, and as a verb, whipping is defined as ‘…beating (a person or animal) with a whip or similar instrument, especially as a punishment or to urge them on’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2023). Despite a persistent reduction in whip offences in UK horse racing since 2010 (British Horseracing Authority, 2016) and the introduction of padded whips with the ability to measure their use and force, the use of whips remains a key welfare issue in racing. Little empirical evidence exists for how whips are used outside of racing despite this being widespread across all ages of equestrians and disciplines. Like with many training aids and practices, understanding how horses learn and react to the cues and signals given to them is critical to ensure an ethical approach to horse training and management. A large-scale survey of 3463 horse riders evaluating whip use identified that generally equestrians owned at least one whip but had poor understanding of learning theory and how this translated to effective use of the whip as an ethical aid; riders who did not use a whip felt using one reflected a deficit in basic horse training (Williams et al, 2019).

This review has focused on the horse and acceptance of the use of horses for sport and other equestrian activities, but it should not be forgotten that a social license to operate incorporates broader concepts than this, as observed in other sectors (Douglas et al, 2022). While equine welfare is a pertinent focus at this juncture, the treatment of the people involved in equestrianism and the impact of equestrian activities on the environment also need to be considered moving forwards. There are analogous issues such as risk of injury and poor mental wellbeing across the horses and people involved in the equestrian sector (Hitchens et al, 2019; Davies et al, 2021). Changing behaviour to promote ethical and evidence-informed practices across equestrianism to align with social license to operate will only occur if the people involved with horses engage with them. An increased understanding of the role of the human within the horse-human relationship to improve knowledge of how human behaviour influences equestrian practice and informs rider and owner decision-making is needed to promote future engagement with education strategies to underpin an evolving social license to operate (Furtado et al, 2021). It is also essential that future research continues to further develop the existing evidence-base to fortify equestrianism's social license to operate (Williams and Marlin, 2020).

The sustainability of routine practice in the equestrian sector, such as flying horses around the world for competition and breeding, how equine waste is managed effectively and the carbon footprint of horse ownership are areas which are already being questioned (West and Malalana, 2020). Again, veterinarians potentially occupy a unique position to help mitigate climate change and other environmental impacts of interaction between humans and horses (Mair et al, 2021). A recent survey of veterinary practices highlighted that the majority of respondents (77%) considered sustainability issues to be extremely or very important, but in contrast only 13% felt knowledgeable or well-informed about practical ways they could promote sustainability in equine veterinary practice (Mair et al, 2021). Further work to support embedding an evidence-based and sustainable approach to equestrian practice will be needed and form a key part of the sector's evolving social license to operate.

Conclusions

A social license to operate is a virtual license from society to engage in an activity; without this the future of equestrianism is under threat. It is essential to secure the future of horse sports and wider equestrian activities that everyone involved within the equestrian sector actively embraces and proactively engages with social license. For equestrian practices to operate legitimately, the management, training and ridden practices adopted with horses should be able to be fully justified and their purpose clearly articulated. This should occur in a transparent fashion without prejudice and without adopting a defensive stance, to showcase to the public how the physical and psychological needs of the horse are managed to provide them with a good life.

KEY POINTS

- There is increasing public scrutiny of horse sports and equestrian activities, and how humans safeguard equine welfare within these.

- A social license to operate is a virtual license given to an industry, sector or sport that permits them to engage in their activities.

- The high-risk nature of horse sports has led to the public questioning equestrianism's social license to operate.

- To maintain a social license to operate, equestrians need to promote practices which give horses a good life, are evidence-based and are transparently communicated to the public to give them trust that the equestrian industry is legitimate and credible in its approach to managing horse-human interactions.

- Increased research to generate the evidence to underpin practice and effective communication strategies to ensure dissemination and uptake by all levels of stakeholder are needed to support the development of equestrianism's social license to operate.