Veterinary medical bandages are used throughout equine practice for many reasons including distal limb wounds, protection of incisions and prevention of oedema and haematoma formation (Canada et al, 2016). The application of bandages, as well as checking and maintaining patency of previously applied bandages, forms a large part of the registered equine veterinary nurse's (REVN) workload. Other types of distal limb support include casts and splints, which are used to provide external support for fractures and for immobilising wounds that lie over joints (Guthrie, 1995). REVNs must look at the equid holistically and move towards a patient-focused approach to nursing. By doing so, problems with bandaging can be avoided while the equid is hospitalised and under the veterinary team's care (Pullen and Gray, 2006). Problems can occur post-discharge, while the equid is being cared for at home (Figure 1), so the veterinary nurse plays an important role in helping to create a home care plan in conjunction with both the veterinary surgeon and owner (Calder, 2014).

Causes of bandaging injury

The causes of injury during the time a bandage is on and once it has been removed can be divided into primary and secondary. Primary injury refers to the time that the bandage is still in place, when there can be interruptions to the blood flow in the tissues. Secondary injury occurs 24–48 hours after the removal of the bandage, when blood flows back into the tissue following a period of ischaemia (Calder, 2014). While primary injury is significant in bandage application because it can cause direct pressure necrosis as a result of a bandage being too tight, secondary injury can occur after the bandage is removed and there is an inflammatory reaction. It is important to be aware of these two mechanisms of bandage injury, as this allows an REVN to become more diligent during both hospital admission and home care. It is the owner or carer's job to check bandages equid post-discharge, but any concerns they have can be addressed by the veterinary nurse, who can make home visits if necessary.

Principles of correct bandaging

There are three basic principles that should be followed to achieve a correct bandaging technique. These are:

- Magnitude of pressure

- Distribution of pressure

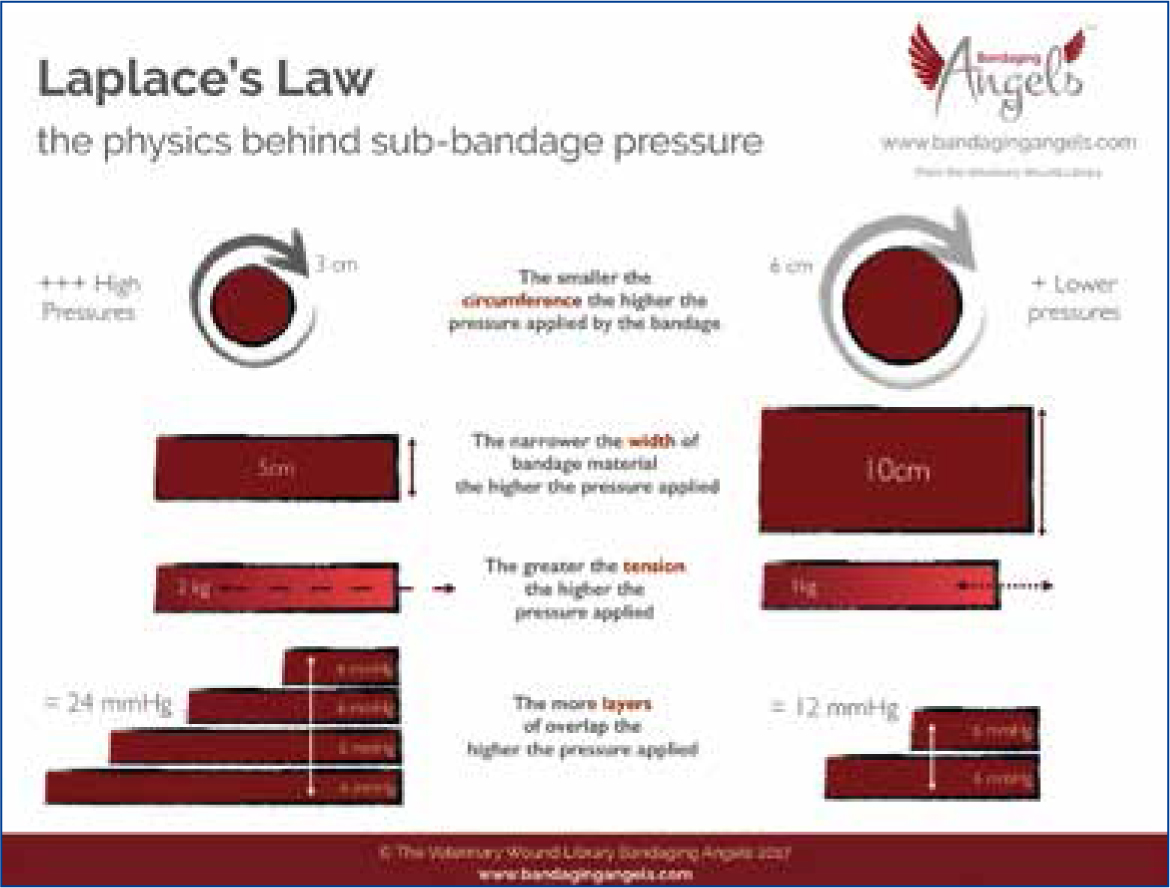

- Application of Laplace's Law (Love, 2000).

Laplace's Law states that tension in the walls of a container is dependent on both the pressure of the containers content and its radius (Figure 2) (Sikka et al, 2016). These principles can be applied to equine bandaging with regards to the location that is being bandaged, because different areas will differ in radius, tension and pressure. For example, the abdomen will vary greatly in comparison to the distal aspect of a forelimb or hindlimb. If these key principles are not followed, equines may present with some clinical signs associated with the development of bandage or cast sores. These include focal areas of increased heat, swelling above the bandage, decreased weight bearing and suppuration above or through the bandage (Levet et al, 2009). This reinforces the importance of correct training for REVNs in bandage application on different anatomical landmarks. Bandaging can be undertaken by anyone with ‘adequate’ training and all involved need to have an understanding of the potential for life-threatening complications. The REVN follows a code of conduct which includes an ethical and moral obligation to themselves, the practice and the general public (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2017). Bandage applications and changes should only be carried out by a suitably trained and competent member of the veterinary team.

There is little research into equine bandaging, which highlights the need for further studies investigating correct technique and different pressures, as well as the need for specific training and education into bandage application and client compliance.

How to resolve bandage complications

In both human and veterinary medicine there are very few reports on iatrogenic injuries, despite anecdotal evidence that bandage-related injuries are relatively common (Anderson and White, 2000). Injuries can range from mild swelling to severe ischaemic injury. The lack of reporting could be for many reasons, for example people might not want to report any mistakes made by either themselves or by their colleagues as this could be damaging to their career. There is an understandable reluctance to report iatrogenic injuries, but it is important to investigate what went wrong, to determine how such situations could be better managed in the future and to avoid the making of similar mistakes (Anderson and White, 2000).

Any concerns with a bandage should be monitored closely by a REVN and reported promptly to the clinician on duty so the REVN can amend the bandage or amend a home care plan for the client (Branscombe, 2008). In equine literature, home care plans for bandaging are often not mentioned and there is no nursing literature on the application and associated complications of bandaging. There are small animal nursing papers that review the importance of home care plans and client information sheets (Calder, 2014) and this is an area which could be carried across to equine nursing, particuarly in terms of outlining potential problems, complications and what signs to look out for, as a REVN would be responsible for putting together the home care plan and ensuring owner compliance (Calder, 2014). In human literature, practical guidelines and step-by-step instructions and pictures are used to help educate practitioners (Gultig, 2005), but these could be adapted for use in veterinary practice and targeted, continuous in-house training would help to prevent bandage complications.

There is currently no objective information in the literature regarding pressures exerted by distal limb bandages in equids (Canada et al, 2016, 2018). The pressure exerted from a bandage can be detrimental to the recovery of a wound by causing tissue necrosis, pressure sores, hair loss or wound contamination. Damage may also be caused by poor application and maintenance of the bandage. It is the REVN's responsibility to monitor and report these complications and take appropriate action, under the direction of the veterinary surgeon.

Compression and correct amount of pressure

The compression and amount of pressure exerted on a limb during the application of bandages has also been discussed extensiely in human medical literature (Khaburi et al, 2012) and more research has been carried out in the humans because of the need to design an effective compression bandage. The use of bandages, with regards to compression therapy, is the first step to managing venous and lymphatic disease in human patients (Todd, 2011). Mathematical models have been developed to try to gain an understanding of what is an effective pressure and how long these pressures remain effective. While this research is related to the control of leg ulceration and oedema in human medicine, it could be applied to veterinary medicine where bandages are used to help reduce oedema either of the distal or proximal limb, or the abdomen (Canada et al, 2015, 2018). Fjordbakk et al (2008) discussed the use of counter pressure bandages to help reduce oedema in cases of cellulitis, in combination with walking exercise in equines, but found that the efficacy of these methods was not known. In human medicine, Khaburi et al (2012) found in an experiment using thin and thick wall cylinders, that the thicker the radius of the limb the less tension or pressure there is. For example, in a limb with a radius of 35 mm the difference in estimated pressure was 1.8%, and the sensors used in the experiment found an average pressure beneath the bandage of 13.7 mmHg. In equine patients, the average circumference of the mid cannon was found to be around 18.1 cm and the average sub bandage pressure was 165 mmHg (Canada et al, 2016) which is significantly greater than in human patients, despite the difference in leg radius. However, it has been suggested that small differences in tension were clinically insignificant (Khaburi et al, 2012). Application of Laplace's Law has indicated that that the pressure underneath the bandage is higher where the limb diameter or bandage used is narrower (Anderson, 2014). This concurs with Khaburi et al's (2012) findings and should be taken into account, depending on the area being bandaged. In small animals, where there is narrowing immediately proximal to the tarsus or carpus or the digits, there is occasionally localised pressure in these areas which can result in a tourniquet effect (Anderson and White, 2000). In the equine patient, the REVN would need to apply appropriate padding to those at-risk areas, which would mainly be any bony prominences, such as the accessory carpal bone or the heel bulbs. Although, it is worth noting that the use of padding can also lead to localised areas of pressure (Khaburi et al, 2012).

Canada et al (2016) conducted a study investigating bandage pressures in the distal limb of equines, using a Picopress to measure pressure. This compression measurer is also used in human studies to determine the pressure exerted on a limb during bandage application. This device could be used by veterinary teams to help determine correct pressures when applying bandages and also to help maintain the optimal pressure throughout the wear of the bandage. Although, a Picopress cannot measure pressures in excess of 189 mmHg and Canada et al (2016) found that the majority of horses maintained pressures in excess of this on the dorsal aspect of the limb. A study of compression devices indicated that the Picopress is a reliable instrument for measuring the pressure beneath a compression bandage (Mosti and Partsch, 2010), but using a measuring device can be difficult in a clinical setting (Anderson, 2014). However, within a clinical setting the device could be used for continuous monitoring, but may not be suitable for use by clients. A study looking at a force sensing array pressure mapping system when applying a Robert Jones bandage, using Laplace's law (an equation) provided correlation charts for the interface pressure, the strain applied and the pattern on the bandage. However, this was carried out using a plastic tube, rather than on patients, possibly giving inaccurate results as a result of the tube being cylindrical and not having the appearance or anatomy of the equine limb (Taroni et al, 2015).

In a study on human patients, Bhattacharya et al (2012) used a bandage lapper to help create a more consistent tension and found that there was only a 0.3% difference in tension between each case. However, only two people were included in this study which does not give the reader an accurate picture of the objective and outcome (Crombie, 1996). The use of a bandage lapper in equine patients would theoretically be a good idea, as different compression levels can be set, but in practice using a machine very close to equines, especially on the distal limb, raises health and safety concerns.

The width of the bandage material used will influence the subbandage pressure as narrow bandage material will produce a higher pressure (Love, 2000). Owing to the nature of the equine limb and abdomen, most of the bandaging materials used are much wider than that of small animal (Figure 3), with conforming materials usually being 150 mm in width and cohesive materials being 10–12.5 cm in width. Although, how much each layer of bandage material is overlapped is also a concern (Wright, 2016). Dale et al (2004) suggested a 50% overlap throughout the bandage, this helps to create an even layering but also is aesthetically pleasing. A mirror can be used to help visualise the medial aspect of the limb when applying bandages from the lateral aspect, although this may not always be feasible within equine practice when taking it to account the health and safety of the equine.

Different types of bandaging materials can have different effects on the pressure exerted during application. The width of the material can affect the amount of pressure exerted, as well as what the material is made out of. In human medicine, it has been suggested that it is important the bandager understands the physical properties of the bandage and also the importance of different bandaging techniques (Lee et al, 2006), which can also be applied to veterinary medicine. Anderson and White (2000) found that bandage material can be divided by its tension:extension curve ratio. Cotton bandage material has a low tension even when it is stretched to 100%, whereas elastic materials will generate high sub-bandage pressures. The effectiveness of compression bandaging will be decided by the properties of the materials used, as well as size and shape of the limb and the bandager themselves (Bhattacharya et al, 2012). Maintaining pressure over a period of time will depend on the properties of the bandage material, with tension forming part of Laplace's law, this decreases over time especially with long stretch materials and between 7–8 hours for short stretch materials (Moffatt, 2008). Movement from the equine patient may affect the number of hours between placement and the bandage stretching and in small animal patients, it has been reported that if the limb is extended or flexed then this will stretch the bandage and cause focal increases in sub-bandage pressure (Anderson and White, 2000). Short stretch bandages have been found to have the highest sub-bandage pressure (Moffatt, 2008; Kumar et al, 2012). During exercise, there are circumferential changes to the limb which affect the effectiveness of the bandage (Kumar et al, 2012), so it is important for the REVN to monitor the bandage for gaps or tearing which could indicate a decrease in pressure and contribute to pressure sores (Smith and Millar, 2012). In human medicine, bandages are applied to help patients suffering from severe superficial venous incompetence and this is not common in equines. However, the use of inelastic bandages could aid in restoration of the venous pumping action to within a normal range, despite the loss of pressure (Mosti and Partsch, 2010). This is a factor which should be considered by all REVNs before equine bandaging, especially for limbs or conditions that do not need the effects of a pressure bandage.

Bandages can have numerous layers, depending on the reason for their application. There can be differing pressures within each layer applied, which can have many differing effects on the limb and can change the outcome of the primary condition the equine presented with. There has been research in human medicine regarding multilayer bandaging and how it can help lymphoedema, but nothing has been published regarding the equine patient. It has been found in human patients that 24 weeks after presentation with lymphoedema, patients that had multilayer bandages applied followed by hosiery had greater reductions in the limb volume than those who did not wear a multilayer bandage (Badger et al, 2000). This research could also be applied to veterinary medicine, with the use of a compression stocking such as Tubigrip, which may help with contralateral limb oedema during the postoperative period following distal limb fracture repair.

Dale et al (2004) found that multi-layered bandages exert pressure from the first two layers and all layers will contribute to the final pressure of the bandage, not just the pressure exerted at the final stage. However, only one human patient was used for this trial and the small sample size makes it difficult to detect clinically important effects (Crombie, 1996). Furthermore, as the bandage materials used were used in human medicine and are not often used within equine hospitals, it is difficult to determine how relevant these results would be to veterinary medicine. During the application of a Robert Jones bandage, as each layer is applied, each layer of padding results in increased tension (Wright, 2016). This should be taken into consideration by the attending REVN on application of any bandage and care must be taken with the application of all layers. It has been suggested that soft, low weight padding is more suitable if pressure reduction is required (Kumar et al, 2015), Robert Jones bandages are frequently used in equine bandaging to provide immobilisation and pressure to a specific area, with cotton wool often being used to bulk up the bandage. Although, consideration should be given to whether a different material should be used.

Recommendations for further study

The lack of research on equine bandaging and complications associated with this is problematic and there needs to be more research into the different pressures exerted on equine limbs while placing a bandage. Currently, there is only one study conducted on distal limbs (Canada et al, 2016) and two on the pressures exerted from abdominal bandaging (Canada et al, 2015, 2018). The abdominal study used a small sample group of nine horses and in future research, to gain more accurate results, a larger sample size should be used. With the help of further research, a combination of a bandage lapper typically used in human research (Bhattacharya et al, 2012) and the Picopress, used in both human and veterinary literature, could be designed for portable and safe use in equine veterinary medicine. To measure pressure, a device could be incorporated into the bandage material itself and an alarm could be triggered to sound if the pressure changed to above or below the recommended threshold. Canada et al (2018) observed the effects of six different types of bandages on the sub-bandage pressures in the equine distal limb, carpus and tarsus in eight healthy horses. The authors concluded that variations to the standard distal limb compression bandage did not increase sub-bandage pressures. However, there needs to be more research into different bandaging materials for use in the equine patient, as well as how these affect the limb in different ways. Research could also be carried out on the most appropriate bandage materials for different types of injuries and whether these have different effects on different breeds across a a variety of limb or abdominal circumferences. This has already been trialled in human research (Moffatt, 2008; Todd, 2011).

The length of time that a bandage is left in place for will depend on the injury and preference of the veterinary surgeon, but there could be guidelines set in place for routine procedures, with reegard to how the length of time affects different types of injuries and conditions or whether the bandage maintains the correct amount of pressure for its use. This has been looked at by Protz et al (2014) for compression bandage systems in human medicine, which found that pressure dropped over time, with a significant pressure drop after 7 days. Research in equine medicine is required to provide further information on the length of time different bandages should remain in place and how this affects wounds and injuries.

Research has been carried out in human medicine on differing positions of the patient for bandage placement, both weight bearing and non weight bearing. Bandage material used that is non-stretch with low elasticity will give the bandager low pressures when the leg is elevated or horizontal, but high pressures when standing (Dale et al, 2004). It is important to consider whether this effect would be the same in animals, as well as whether a bandage placed while the horse is recumbent on the surgery table would be different to one that is applied while weight bearing. The amount of exercise and movement also has an effect on bandage application, how effective that bandage is and the time between bandage changes, which has also been researched in human medicine (Kumar et al, 2012). The effects of exercise and movement differ greatly in the equine patient, so there needs to be research into how to prevent bandage movement and pressure sores, as well as which bandage would suit different levels of exercise, for example box rest or hand walking exercises during return to work.

Recommendations for veterinary practice

There should be bandage protocols and written instructions for clients, including a practical demonstration by the nurse applying the bandage the day before the equine is discharged, followed by the client being asked to demonstrate placing the bandage before discharge. This would help to get the client more involved and allow them to ask any questions about the bandage, with any mistakes they make being corrected by the nurse. Doing this would hopefully help to prevent and eventually stop bandage complications at home. Compliance from both the owner and the equine are vital to the success of correct bandage placement and maintenance. Written instructions given to the client should be clear and have a picture of what each stage should look like, with a finished picture of how the bandage should appear at the end of the instructions. The option of a video could also be available, which could be accessed online at any time.

Bandage protocols also need to be utilised for each member of the veterinary team. A step-by-step guide to bandage application, a guide to applying different types of bandages, including what materials to use and how many layers of each, and a picture guide may help to give an idea of what the final bandage should look like. A video may also prove useful for new members of staff, as time to teach new staff may be limited.

Care plans for bandages may prove useful to learning how to assess pain, heat, swelling, discharge, smells, strike through (Figure 4) and correct limb positioning throughout the application. These learning materials could be utilised within the practice, but also given as part of a home care plan for owners once the equine has been discharged. The use of pictures and videos would aid with limb positioning and learning how to number grade pain, as well as identify swelling and strike through would help both the nurse and client determine the severity of these and indicate when a veterinary surgeon should be notified. Client education evenings could be held for practical demonstrations on either a model or live horse, which could be done in conjunction with the use of a compression measuring device that enables clients to gauge how much tension and pressure should be applied to each layer. This could be carried out at the client's yard or stable as part of a routine visit.

Conclusions

There is limited research conducted on the factors that cause bandage complications in equine patients. There are two studies that looked at distal limb and abdominal sub-bandage pressures, but these two papers alone cannot be used to fully validate the research outcomes or make an impact on changes in equine practice. There is an abundance of research and tools for training, application and maintenance of bandages in human medicine, from which equine medicine can adapt a variety of methods and procedures. This research draws similar conclusions on the use of wider bandage materials, correct amount of overlapping, multilayer bandaging and similar compression monitoring, all of which could be adapted for safe use within equine veterinary practice.

KEY POINTS

- There is a lack of research available on the effects of equine bandaging.

- Human research on bandaging can be adapted for use within the equine veterinary industry.

- The registered equine veterinary nurse plays a key role in the placement and management of bandage application.

- Adequate training and protocols should be set in place to help prevent bandage complications within a hospital setting and in the equine's home environment.