Foreword

This document was commissioned by UK-Vet Equine to provide veterinary surgeons with up-to-date information on equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy in the wake of the outbreaks that occurred in Valencia and subsequently across Europe and the Middle East in 2021. The content of the document and practical recommendations were developed from discussion between the authors, considering published and unpublished research relating to EHV using a roundtable forum and online discussion. Where research evidence was conflicting or absent, collective expert opinion of the group was applied. The opinions expressed are the consensus of views expressed by the authors who all approved the final manuscript. Where an agreement was not reached, diverging views are presented. The expert group was organised by UK-Vet Equine and the meeting held online on 10th June 2022 with sponsorship from Zoetis. The sponsors were not involved in the production of the manuscript.

Why should we be concerned about equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy?

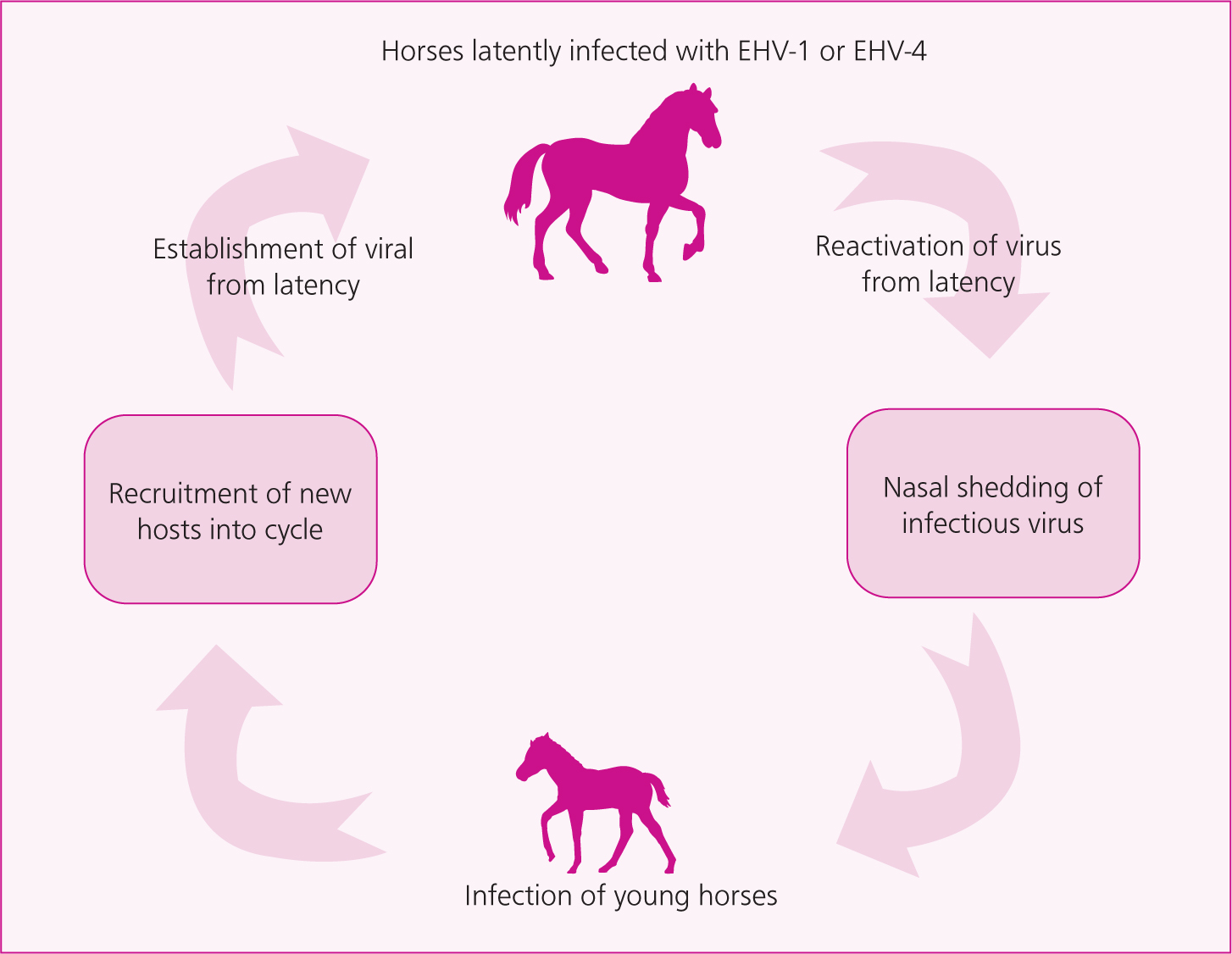

There are nine different equid herpesviruses (EHVs); five types (EHV-1 to EHV-5) infect the domestic horse and four, EHV-6 to EHV-9, are associated with infections in wild equids and other perissodactyl including asses, zebra and rhinoceros. The alpha herpesviruses EHV-1 and EHV-4 are respiratory pathogens, and EHV-1 also has the potential to cause outbreaks of abortion and neurological disease. EHV-1 is a highly successful host-adapted equine pathogen with a complex life cycle that enables its spread and persistence within the global horse population. It is believed that there is early and widespread infection of youngstock which, combined with persistent infection coupled with recrudescence (latency and reactivation), ensures endemicity and the somewhat unpredictable manifestation of clinical disease in the UK and globally. The spread and persistence of the virus is not dependent on clinical disease and silent transmission is common, allowing transmission down equine generations and persistence within herds.

Outbreaks of equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM) can have high rates of morbidity and mortality (Henninger et al, 2007; Pusterla et al, 2010) and treatment is often unsuccesful in severe cases. Within a stabled population, rates of infection and neurological disease may be as high as 80% and 40% respectively (Henninger et al, 2007). Any horse can be a latent carrier (Figure 1), so all horse movements carry a risk of triggering reactivation and nasal shedding of virus, although the overall risk of reactivation and recrudescence from latency with subsequent transmission appears to be low. The occurrence of clinical outbreaks is sporadic and unpredictable, and all horses are vulnerable to disease. Outbreaks of EHM have resulted in the cancellation of gatherings, placing restrictions on horses and forcing the closure of some equine hospitals (Vandenberghe et al, 2021), with associated economic consequences. Veterinary surgeons, organisers of equestrian gatherings and horse owners have a shared responsibility to minimise the risk of EHV-related disease, while recognising that the risk can never be eliminated. EHM is reportable or notifiable in many countries, although not the UK.

Aetiopathogenesis of equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy

The virus rapidly enters respiratory epithelial cells and readily infects cells of the local lymphoid tissues, such as monocytes and lymphocytes in the upper respiratory tract, with infected leucocytes ultimately establishing a cell-associated viraemia (starting as early as day 3 post-infection), disseminating the virus to sites of secondary replication including the endothelium of small blood vessels within the spinal cord and/or the uterus of a pregnantmare. Endothelial cell infection results in cell extravasation, vasculitis and thrombus formation, which results in hypoxia and subsequent axon swelling as well as haemorrhage, with the extent and location of the neurological lesions determining the nature and severity of clinical signs (Table 1). Longer motor neuron pathways are more likely to be affected, which explains why the symptoms of hindlimb ataxia and inability to open the bladder to urinate (with resultant overflow incontinence) are the most frequently reported clinical signs.

Table 1. Clinical signs which may develop in association with equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy

| Anatomical area | Clinical sign |

|---|---|

| Limbs | Temporary ataxia and paresis which may or may not progress to quadriplegiaDragging toes of hind limbs when moving on a figure of eight Hindlimb incoordination |

| Bladder sphincter dysfunction | Dysuria and inability to pass urine |

| Cranial nerve signs (uncommon) | Head tilt, nystagmus, facial twitching |

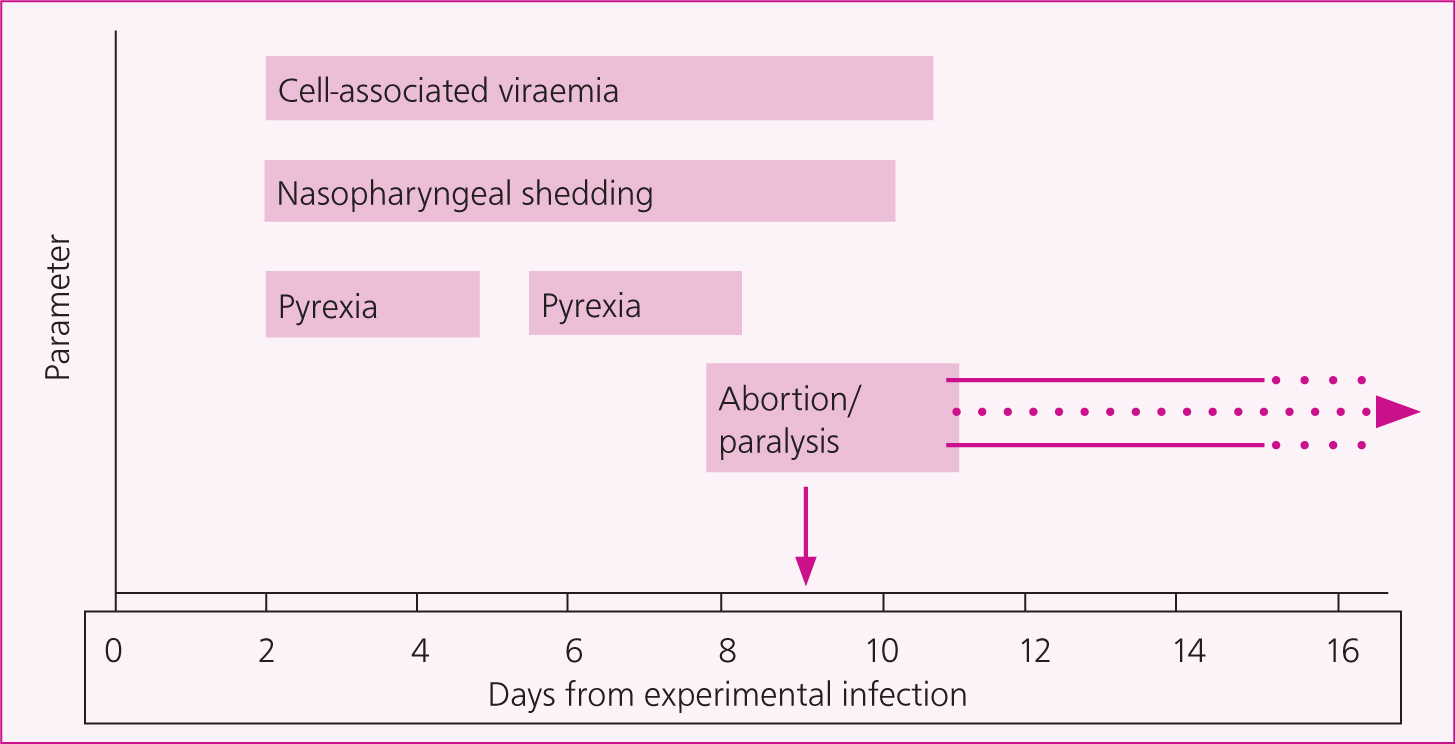

In young, naïve horses, EHV-1 usually causes a biphasic pyrexia (Figure 2), but these temperature increases are rarely detected unless routine temperature monitoring is under-taken. In older horses with more robust immunity, the initial phase of infection may not be evident clinically, and pyrexia may not develop until there is viraemia around 3–5 days post-infection. Therefore, viral shedding and disease transmission can occur before there is clinical evidence of infection. The severity of clinical signs is unpredictable in individual animals, but is the consequence of a complex combination of the virulence of the virus strain, host genetics, infectious dose, level of cell-associated viraemia, degree of ischaemia and consequent pathology, host immunity and degree of immune response. Increasing age also appears to be a risk factor for EHM (Henninger et al, 2007).

Risk factors for equine herpesvirus-1 infection

EHV-1 typically spreads slowly within a population, although the spread can be more rapid if infected horses with respiratory signs are in close contact and there is greater potential for smear infection or direct transmission. Airborne spread will occur over distances of a few metres, with the risk increasing if horses are coughing and sneezing. However, these signs may not always be evident. Indirect spread may occur via people and fomites, for example with the use of shared equipment or tack. The risk of infection will also be increased by:

- Absence of precautions taken when introducing or mixing horses

- Mixing horses from different sources, particularly young horses

- Mixing horses that have been subject to recent stressors, such as transportation

- Having large numbers of horses in a shared airspace

- Poor ventilation

- Sharing of equipment, especially tack, without appropriate cleaning and disinfection

- Human contact with multiple horses from different sources, without appropriate sanitary measures.

Where several of these risk factors occur concurrently, the risk of infection increases proportionally (Traub-Dargatz et al, 2013).

Recent historical perspectives

In February 2021, an EHV-1 outbreak associated with a high proportion of horses suffering from EHM occurred in Valencia, Spain at a large show-jumping competition, resulting in the reported deaths of 18 horses in mainland Europe over a 4-week period and 31 related EHV-1 outbreaks across 10 countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Qatar, Spain, Slovakia, Sweden and Switzerland. The full report of the outbreak produced by the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (FEI) is available at https://inside.fei.org/fei/your-role/veterinarians/biosecurity-move-ments/biosecurity/ehv-1/report. All international FEI events were cancelled in continental Europe from 1 March to 11 April, including the World Cup Finals, and 3836 horses in the FEI database were blocked from further competition until they had fulfilled the FEI's health requirements to demonstrate freedom from infection.

The virus was subsequently identified to be A2254/N752 genotype, a strain which commonly circulates in Europe and would not normally be considered particularly pathogenic. Specifically, the virus identified did not have the G2254/D752 nucleotide/amino acid substitution in the DNA polymerase that had previously been shown to be associated with a higher risk of neurological disease. Between the end of January and 21st February, over 700 horses passed through the Valencia event, with many of the horses spending several weeks on site. Many of the horses attending the event had travelled for days to reach the event. The outbreak started in temporary tented stables that had closed sides, limited ventilation, and contained over 400 horses housed in rows of 20 with 3.5m wide aisles between rows (Figure 3).

The limited ventilation and high number of horses within the airspace may have led to extremely high levels of virus circulation, meaning immunity, if present, was overcome. The location of horses within the stables was found to be associated with a higher risk of infection. Horses that were outside the stabling or on the periphery facing out were six times less likely to develop pyrexia and nine times less likely to develop neurological signs (Couroucé, unpublished data).

Recommendations for the protection of competition horses

The FEI conducted a comprehensive and fully transparent investigation into every aspect of the EHM outbreak that occurred in Valencia in 2021 (Termine et al, 2001) and their three part report is available on the FEI website (FEI, 2022).

- Part 1 provides a comprehensive and factual description of the outbreak, including the series of events, causes, roles and responsibilities, and analysis. It evaluates what was done correctly and identifies where there were failings, and the lessons learned

- Part 2 covers the measures implemented to allow return to competition following the 6-week FEI-imposed lockdown on international sport in mainland Europe

- Part 3 looks at the way forward, including potential global vaccination protocols.

Other resources offer advice on minimising the risk of EHV-1 transmission:

- National Trainers Federation codes of practice: https://www.racehorsetrainers.org/publications/pdfs/cop.pdf

- Horserace Betting Levy Board codes of practice: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/index.php/page/32, which is also available via the EquiBioSafe App (https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/equibiosafe/id1131137694)

- American Association of Equine Practitioners and US Department of Agriculture guidance: https://aaep.org/guidelines/infectious-disease-control/equine-herpesvirus-resources

- British Equestrian Equine Infectious Disease Advisory Group notes: https://www.britishequestrian.org.uk/equine/health-biosecurity/advice-notes-for-equine-gatherings (Box 2)

- FEI horse health requirements: https://inside.fei.org/fei/your-role/veterinarians/biosecurity-movements/horse-health

Measures implemented by the International Federation for Equine Sport following the Valencia outbreak

In the wake of the Valencia outbreak the FEI introduced measures that, in the short term, aimed to minimise the risks of further propagating the spread of EHV-1 infections associated with the restart of FEI competitions in continental Europe and, in the long term, aim to increase biosecurity knowledge, skills and awareness among all FEI stakeholders in order to prevent future EHV-1 outbreaks:

- Tour venues were risk-assessed and biosecurity protocols for events reviewed

- Foreign veterinary delegates, appointed by the FEI, will attend high-risk events

- FEI jurisdiction during and after events was extended so that it has greater powers to implement disease control measures

- The FEI recommended that National Federations extended their jurisdictions to ensure they had the authority to shut down events should it be necessary to do so.

The FEI HorseApp that had already been in development was brought into operation to enable recording of:

- Examination findings on arrival at venues

- Recording of rectal temperatures before and during an FEI event

- Digital submission of the FEI equine health self-certification form

- PCR test results

- Equine whereabouts information

The procedure for veterinary examination of horses at the entry to events was bolstered by the introduction of the HorseApp, as this provided a clear evidence trail for examination having been carried out on arrival. Mandatory recording of entry examination findings in the FEI HorseApp by an FEI veterinarian was required, alongside GPS location of the horse's microchip.

Twice daily temperature monitoring became mandatory at FEI competition from April 2021 and is facilitated by the FEI HorseApp in which recordings must be entered.

The protocols for management of suspected cases and the resourcing of isolation stables at events have been enhanced. Access to laboratories with PCR equipment is limited, particularly on weekends, and the FEI has urged the development of stable-side PCR tests for EHV-1 that can be used systematically at competition venues.

The FEI also highlighted a need to fund an Emergency Response Unit that could be deployed to support any National Federation immediately if a disease outbreak is confirmed at an FEI Event. The unit will include veterinary surgeons with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In the UK, the British Equine Federation's emergency response group (BEFERG) is on stand-by to lead decision-making in the event of an outbreak.

Article 1018 of the 2020 FEI Veterinary Regulations already requires that organising committees:

- Develop a biosecurity plan for all events

- Maintain records of where horses have been kept in stables

- Make contingency plans and determine adequate provision for isolation facilities

Post-Valencia, the FEI has highlighted the importance of:

- Having mitigation plans for outbreaks of infectious disease at all events

- Accessing PCR testing for EHV-1 for horses arriving at designated events

- Minimising nose-to-nose contact through the use of partitions that are at least 2.4m high, implementing one-way movement of horses through venues and preventing horses from lingering in aisles during preparation, grooming and mucking out

- Applying basic hygiene procedures such as regular hand washing and cleaning of footwear and equipment

- Controlling dogs at events.

Box 1.Recommendations made by the British Equestrian Federation's equine infectious disease advisory group for the prevention of spread of equine herpesvirus at equestrian eventsMeasures should be implemented to prevent the entry of:

- Any horse with a recent cough, nasal discharge of unknown cause, enlarged lymph nodes or a fever

- Any horse which is known or under investigation for equine herpesvirus infection (whether associated with respiratory or neurological signs).

- Any horse which has been in contact with, or lives on the same premises as, a horse known to have or be under investigation for equine herpesvirus infection associated with neurological signs.

- Where a horse has been excluded due to neurological EHV or neurological EHV-contact, future admission should require that:

- EITHER all horses on the property have close clinical monitoring with twice daily temperature recording and the excluded status should apply until all horses on the premises have been free of clinical signs for at least 28 days.

- OR a detailed veterinary report should be presented to the BEF-MB EID veterinarian including robust laboratory evidence to show that the horse intended for admission to a gathering has not been infected with neurological EHV

EIDAG suggests this is implemented via a “health and freedom from disease & contact” declaration. The BEF-MB's EID veterinarian should be available to support attending veterinary surgeons if required.

Should equine herpesvirus-1/4 vaccination be mandatory for horses attending events?

In the UK, inactivated EHV-1 and -4 vaccines are registered for ‘active immunisation of horses to reduce clinical signs due to infection with EHV-1 and 4 and to reduce abortion caused by EHV-1 infection’ and have been shown to reduce the incidence of abortion and virus shedding (Hannant et al, 1993; Goehring et al, 2010; Walle et al, 2010; Heldens et al, 2001; Schabel et al, 2019). Vaccination reduces the number of horses which develop viraemia and shed the virus (Heldens et al, 2001). Therefore, use of vaccines may lead to a reduction in virus circulation in the population and this, in turn, may reduce the risk of EHM both at an individual and herd level. However, there are no robust data that vaccination reduces the risk of EHM and appropriate studies have not been performed, largely owing to the absence of a relevant experimental equine model of this disease syndrome until relatively recently. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of commercial or candidate vaccines against EHV-1 in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was performed recently (Marenzoni et al, 2022). Meta-analysis of 16 eligible RCTs reported in eight studies concluded that EHV-1 vaccination generally resulted in a slight improvement of clinical and virological outcomes, although not to a significant extent (Marenzoni et al, 2022).

The case for vaccination in the control and prevention of EHM is equivocal, as analyses of some previous outbreaks have demonstrated a significant association between the use of EHV vaccination among outbreak populations and greater frequency of EHM (Traub-Dargatz et al, 2013). Unpublished data from 157 horses that remained at the venue during the Valencia outbreak showed that, compared to non-vaccinated horses, horses that were vaccinated were more likely to die (12% vs 3%; P=0.036), more likely to develop EHM (23% vs 11%; P=0.04) and more likely to develop EHM and/or fever (88% vs 60%; P=0.001) However, there was no significant corresponding difference in EHV-1 infection prevalence (by PCR) between these groups (49% vs 48%; P=0.95) (Cunilleras, 2021). Although, it is cautioned that this should not be assumed to be a causal association as there needs to be appropriate consideration of confounding factors, such as age and spatial or temporal clustering of horses within enclosed airspaces, leading to marked variation in load and duration of viral exposure. Most of the participants in this roundtable consider that the use of a vaccine containing an inactivated EHV-1 strain following exposure does not increase the risk of clinical neurological disease, and anecdotally, some horses were reported to have been vaccinated in the face of potential exposure in Valencia with no apparent increase in frequency of EHM.

While with the currently available products, vaccination in horses that have potentially been exposed to EHV-1 is generally not considered to be contraindicated, some of the authors do not consider it to be beneficial for practical reasons, such as:

- Time taken to stimulate immune protection

- A false sense of protection from the risk of EHM and EHV-1 infection, with the risk of lapses in maintaining biosecurity measures

- Interference with serological assay interpretation complicating the use of these tests to aid outbreak clearance

- Vaccines have not been registered for this indication

- Theoretical possibility of such use of EHV-1 vaccine-triggering clinical disease, although this has never been reported in practice and, in the view of some of our expert panel, is unlikely with a vaccine containing an inactivated viral strain.

In France, mandatory EHV-1 vaccination was introduced for broodmares in 2015, Thoroughbred racehorses in 2018 and for Standardbreds in 2019. Mandatory vaccination was imposed by the US Equestrian Federation in 2018, and the German Equestrian Sports Federation is set to impose mandatory vaccination for horses competing under their rules. The Société Hippique Française has imposed mandatory vaccination for horses up to 3 years of age.

The FEI has currently stopped short of mandating compulsory vaccination for horses competing under their rules and are keeping the situation under review. A particular challenge to implementing mandatory vaccination by a global regulator like the FEI is ensuring the availability and consistency of vaccine supplies across different countries; 20 FEI member national federations reported an absence of registered vaccines, 33 of 73 reported periodic interruptions in vaccine availability, and in two countries, vaccination is reported to be prevented by legal restrictions.

The British Equestrian Federation does not mandate EHV-1 vaccination, but recommends that the following groups of horses be re-vaccinated against EHV-1 or -4 at 6-month intervals in accordance with the manufacturers' recommendations (https://www.britishe-questrian.org.uk/equine/health-biosecurity/advice-notes-for-equine-gatherings):

- Horses less than 5 years of age (but older than 6 months)

- Horses that may come into contact with pregnant mares

- Horses housed at facilities with frequent movement of horses on and off the premises

- Horses that frequently attend gatherings where horses mingle in close proximity.

For EHV-1 or -4 vaccination to be effective, booster doses are required at 6-month intervals. In some populations, vaccines are being used ‘off-label’ (and without proof of efficacy) as frequently as every 2 months, with booster vaccinations of all in-contact and at-risk horses being performed in the event of EHV-1-related disease (Goehring, personal communication).

Research into new vaccines that may offer greater protection is required; however, vaccination will never provide complete protection from disease. Herpesviruses are adept at evading host immunity through multiple immuneescape molecules they encode and through latency. Hence, infection does not result in long-lasting natural immunity. Therefore, it is unlikely that it will be possible to achieve the level of herd immunity that is theoretically possible with vaccination for some other diseases. Vaccination will not eliminate the need for effective biosecurity and other disease control measures. While there is a risk that vaccination may result in complacency with respect to the need for additional biosecurity measures, it may alternatively reinforce the need for compliance with other infectious disease control measures.

Additional recommendations

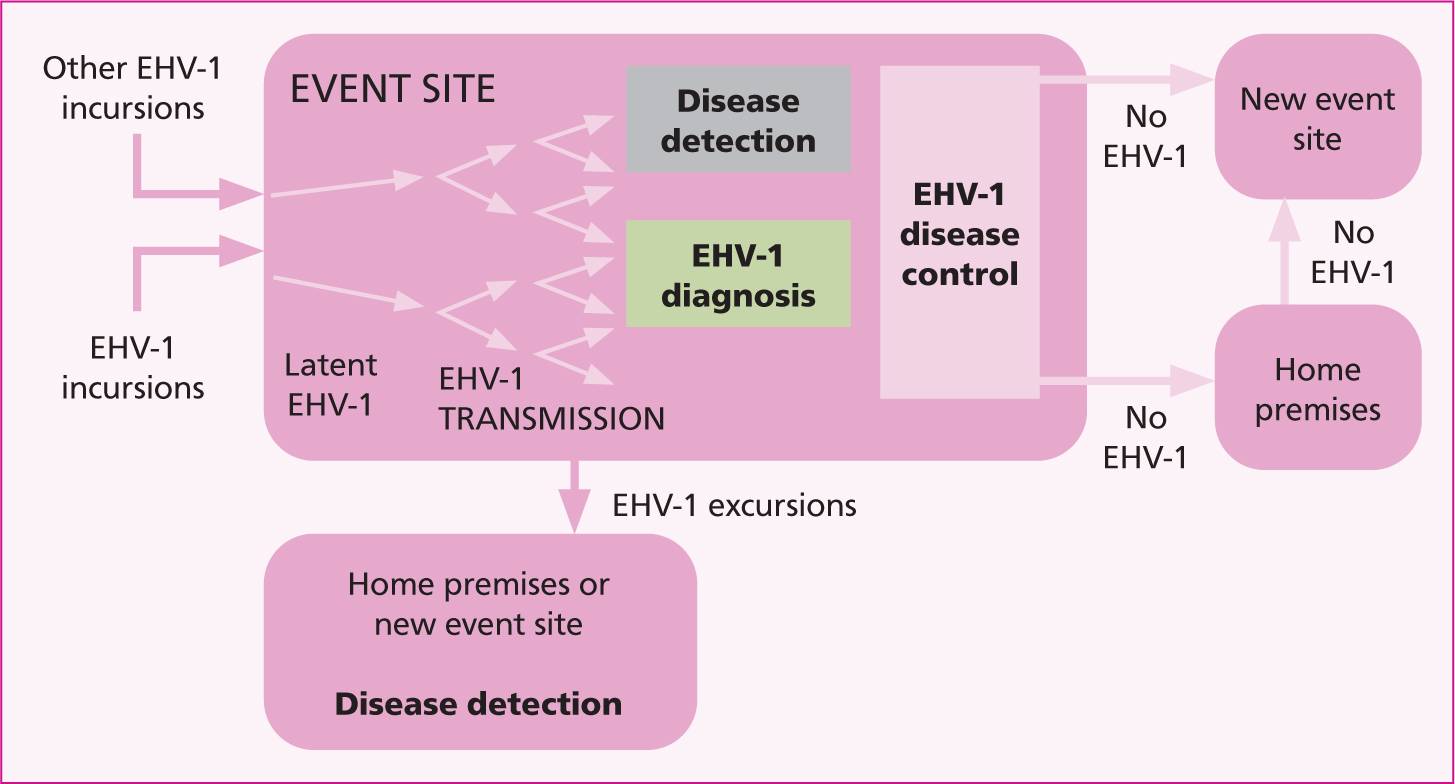

Large equestrian gatherings over multiple days pose an increased risk of EHV-1 outbreaks, and there is then a high likelihood of further outbreaks at connected equestrian competition venues if additional measures are not put into place. Anecdotally, the number of reported EHV-1 and EHM cases appears to be increasing, which raises concerns that infections are becoming more common because of greater numbers of horse movements over increasing distances, although this may also be linked to enhanced investigations with improved diagnostics and online reporting.

There is a trend of increased prevalence in larger equestrian facilities and events with greater numbers of horses housed on the same premises. If further outbreaks, such as Valencia 2021, are to be prevented, then consideration needs to be given to additional measures that can be implemented before, during and after competition to reduce the risk of infectious transmission on and away from event sites to home premises and other event venues (Figure 4). Many of these measures have already been implemented, or are under consideration by the FEI, and the introduction of the FEI HorseApp is a major step forward.

Critical control points for equine herpesvirus myeloen-cephalopathy prevention

Pre competition – horses

Additional measures can be implemented to reduce the risk of horses with clinical or subclinical EHV-1 infection attending equestrian gatherings. Placing a responsibility on competitors to declare that their horses have been free from clinical signs (and have been free from contact with horses with clinical signs) should help to prevent horses at high risk of transmitting EHV-1 from travelling, and would serve as a reminder to competitors of the risks of infectious disease transmission at competitions. Caretakers should be encouraged to vaccinate their horses strategically to ensure that levels of immunity are likely to be high at the time of travelling and competing.

Pre-competition – facility

The FEI report on the Valencia outbreak high-lighted potential inadequacies in the procedures for veterinary inspection of horses on arrival at events (FEI, 2022). Where possible, veterinary inspection of all horses, including assessment of rectal temperature, should take place before admission to the competition venue. To be effective, there must also be a workable plan for how to deal with any horse arriving at a venue with a fever, in a manner which ensures it can receive appropriate veterinary care without endangering others. The site of inspection, and associated isolation facilities, should be separate from the main competition venue.

Limiting the number of horses and maximising the ventilation within each airspace in the event venue will limit the risk of disease transmission. More guidance should be provided to event organisers on the requirements for stabling at competition venues, with equine biosecurity and welfare being prioritised over other considerations.

Every competition venue should have a contingency plan for each event that considers the levels of risk and makes provisions for managing disease outbreaks accordingly.

Horse monitoring during competition

It is recognised that compliance with recommendations or requirements for manual temperature taking is very poor and is unlikely to improve whatever measures or regulations are put in place. There is a compelling argument for the use of temperature monitoring microchips that can be used to collect individual horse temperature data either by athletes or veterinary officials. If all horses were required to have temperature monitoring microchips or use wearable temperature monitors, every horse at a venue could be checked very quickly with the data constantly monitored. Time would also be saved at entry inspections, as these devices would generate a continuous temperature diary which could be reviewed retrospectively if necessary.

Isolation facilities and protocols

Isolation facilities are rarely adequate at competition venues and thus need greater consideration. The recommendation in the FEI Veterinary Regulations is the provision of two isolation stables, with an additional one for every 100 horses and a contingency for over-flow isolation facilities.

Depending on the size and level of risk at the event, isolation facilities may need to allow multiple different groups of horses to be isolated from one another. The number of isolation stables required should be dictated by the size of the event and may be reduced if other biosecurity measures (such as vaccination, athlete declarations, veterinary inspections on arrival, remote digital temperature monitoring and appropriately designed stabling) are implemented appropriately.

Isolation stabling would not need to be permanent, but there needs to be a contingency for prompt referral of horses and samples to appropriately equipped veterinary hospitals and laboratories, respectively, and potentially for the rapid erection of extra temporary stabling should the need arise.

Verifying freedom from infection after EHM outbreaks

Further consideration needs to be given to the requirements for verifying freedom from EHV-1 infection and to aligning protocols across different organisations and events, where this is to be adopted. Repeated negative test results (PCR and paired serology testing) are considered to provide robust evidence of freedom from infection (Gonzalez-Medina and Newton, 2015). However, in the Valencia outbreak, some horses returned negative PCR results before subsequently becoming positive. The cycle threshold value for any PCR result is important, as is knowledge of the biosecurity measures that are in place to minimise the possibility of re-infection.

Owing to the very high sensitivity of PCR, care needs to be exercised to reduce the risk of cross-contamination when multiple horses are being sampled. In the UK, complement fixation tests that measure antibodies against EHV-1 and -4 are used alongside PCR to provide additional assurances of freedom from infection. Paired complement fixation tests and PCRs were used successfully in laboratory screening of 195 horses undergoing quarantine on returning to the UK from Valencia and the Sunshine Tour in 2021, thereby preventing incursion of EHV-1 infections.

Consistency of messaging around the number and type of nasal or nasopharyngeal swabs that are required, and the testing interval may improve compliance with testing protocols. Three swabs are often taken, although only two swabs are recommended if complement fixation tests antibody tests are used concurrently as a retrospective measure of exposure (Figure 5). Swabs have been taken up to a week apart, but at a competition venue where there is pressure to get horses home, this may be impractical and intervals as short as 24-hours have been advocated for in some situations.

Protocols may need to be different for horses with confirmed infection versus those that have potentially been exposed to infection. There is a need for testing that can return results more rapidly and be available 7-days per week. Stable-side testing kits that can be used by veterinary delegates would reduce the logistical challenges associated with the use of external veterinary laboratories, but their accuracy is yet to be determined and they will require rigorous validation of their application in the field. This is a fast-moving area and will need to be reviewed frequently as data become available.

Wider considerations

There is a need to educate horse owners and event organisers regarding the risks of infectious disease. Competition organisers and athletes are frequently complacent about the risks and are reluctant to implement measures that are perceived as inconvenient. Risk messaging needs to be simple, concise, and constantly repeated, and is likely to have more impact from key opinion leaders within the equestrian community, than from veterinary surgeons or scientists. There is also scope for improving veterinary education. It will be important to engage with social scientists on how veterinarians can communicate more effectively with horse owners and embrace technologies, such as implanted temperature monitoring microchips, especially where social science research indicates that human behaviour will not change as it needs to.

Conclusions

The events of 2021 highlighted the welfare implications and economic impacts of equine EHV-1 infection and its most severe clinical manifestation, EHM. This condition is a threat to all horses, particularly competition horses that are subject to periods of stress and frequently gather with large numbers of other horses. While there is no clear evidence that vaccination prevents the development of EHM, it is logical to assume that increasing the use of vaccination should reduce the amount of virus being shed into the environment and hence reduce the potential for clinical disease. However, EHV-1 has a complex natural ecology with the horse and the impact of vaccination will need to be kept under review. At best, it will only ever reduce the risk and will always need to be part of improved husbandry and enhanced biosecurity strategies at equine gatherings.

Key points

- Equine herpesvirus is endemic and there is a constant risk of reactivation of infection in horses with latent virus

- Stress is a major risk factor for reactivation

- Rates of morbidity and mortality can be high in disease outbreaks

- Veterinary surgeons, horse owners and organisers of equestrian gatherings have a shared responsibility to minimise the risk of equine herpesvirus-related disease

- Viral shedding and disease transmission can occur before the development of clinical signs

Key points

- EHV-1 and -4 vaccines have been shown to reduce the incidence of abortion and to reduce virus shedding

- Vaccination reduces the number of horses that develop viraemia and shed virus

- There are no robust data that EHV reduces the risk of EHM

- The use of EHV vaccination has been associated with the development of EHM in some outbreaks, but the evidence has limitations and the association may not be causal

- Most of the authors consider that the use of an inactivated EHV-1 vaccine does not increase the risk of EHM and, through reduction of virus shedding, should reduce the risk of EHM at equestrian gatherings.

Key points

- Historical and clinical data (particularly rectal temperature) should be considered before horses are admitted to equestrian gatherings

- All equestrian gatherings should have the facilities to quarantine incoming horses and isolate horses that develop signs of infection during competition

- Limiting the number of horses and maximising ventilation within each airspace will reduce the risk of disease transmission

- Every competition venue should have contingency plans in place prior to the event

Key points

- There is a compelling argument for the use of temperature monitoring microchips in horses attending equestrian gatherings

- Further consideration needs to be given to the requirements for verifying freedom from infection

- There is a need for validated testing that can return rapid results to be available 7 days per week

- Horse owners need to be better educated of the risks of infectious disease and on how to implement effective biosecurity measures